It is easier to act yourself into a better way of feeling than to feel yourself into a better way of action.

–O.H. Mowrer

OUTPUTS ARE FUNCTIONS OF INPUTS

A STRATEGY TO OBSERVE HOW THE SEEDS YOU SOW MANIFEST INTO THE FRUIT YOU DESIRE

The best place to succeed is where you are with what you have.

-Charles Schwab

The input-output chart, a.k.a. reward chart is a CBT method for observing the influence our efforts have in reaching our desired outcomes.

- It is based on the functional model of healthcare.

- The functional model of healthcare has three assumptions:

- That there is collaboration between the health care provider and the patient

- That the patients’ problems arise from interactions between patients and their environment, including responses to the problem themselves

- Improvement is correlated with patients’ efforts between sessions

- It’s goal is to figure out a set of behaviours that change the patients, their environments, and/or interplay between them

- With this change, their is a change in the outcome

- We choose activities that are likely to result in desirable outcomes, and then modify the process ad hoc

- There is evidence for this process:

- The tight linkage between remembering the past and imagining the future has led several investigators to propose that a key function of memory is to provide a basis for predicting the future via imagined scenarios and that the ability to flexibly recombine elements of past experience into simulations of novel future events is therefore an adaptive process (e.g., Boyer, 2008; Schacter & Addis, 2007a, 2007b; Suddendorf & Corballis, 1997, 2007)

A. Filling out your Outputs/Rewards: What is your desired outcome?

- If you have difficulty imagining what would be good, a convenient starting point is the opposite of what is bad currently in your life.

- While situations may be bad, we have influence over our behaviours and emotions. So, we would pick an emotion as our desired outcome (Output/Reward).

- Examples of the connection between emotions and problem situations where the emotions are italicized.

- “I can’t ride my bike.” ⇒ I feel sad.

- “I have no one to talk to.” ⇒ I feel lonely.

- “I can’t figure out this online booking system.” ⇒ I feel inadequate.

- “I’m damaged by this injury.” ⇒ I feel hopeless/despair.

- “I’m a burden on my partner.” ⇒ I feel worthless.

- Examples of problems, and their corresponding desired outcomes (in bold):

-

- If you are sad, then the goal will be to do things that result in more happiness.

- If you are lonely, the goal will be to do things to allow you to feel a sense of belonging.

- If you feel you are helpless, the goal will be to be to do things to feel more competent.

- If you feel hopeless, the goal will be to do things that increase your hope.

- If you feel unlovable, the goal will be to experience loving encounters to increase your self-esteem.

-

- Stick to just 1 or 2 goals, or you will likely lose focus.

B. Filling out the Inputs/Efforts Section: What commitments will you make to work towards your desired outcome?

- Common things patients choose are compliance with treatment recommendations, physical exercise, being more social, improving their diet, committing to “me time”, improving their sleep, etc.

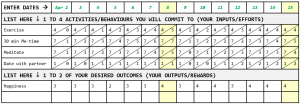

C. Filling out the date

- Each column is headed by a date.

D. Filling out the diagonally split boxes in Section “ACTIVITIES/BEHAVIOURS YOU WILL COMMIT TO (YOUR INPUTS/EFFORTS)”

- In the top triangle, enter the number of times you aim to commit to doing that row’s input per week

- Note: The 7th day of each week is highlighted in yellow to make it easy to see how you performed for that week.

- In the bottom triangle, enter a running tally of the number of times you did that row’s input for the week.

E. Filling out the boxes in the Section “YOUR DESIRED OUTCOMES (YOUR OUTPUTS/REWARDS)”

- Enter the state of that desired outcome on a scale of 0-10, 10 being the most of the desired emotions/sentiment you have ever experienced, and 0 being the opposite of that.

Review of this table

A. The patient committed to doing the following activities to increase their happiness:

- Exercising regularly, with a frequency of 4x/week

- Carving out 30 minutes of “me-time” every day.

- Meditating daily.

- Having a “date night” with their partner 1x/week.

B. The patient was able to achieve the following “quotas”

- Exercising: In week 1, they surpassed their quota; In week 2, they met it.

- “Me-time”: In week 1, they met their quota (7x/week); In week 2 they fell two “Me-time” sessions short of the mark (7x/week).

- Choosing to do something 7 days per week can be challenging at first and it may be better to choose a more modest goal.

- Meditating: In week 1 they fell 2 sessions short of the mark (7x/week); and in week 2, they needed to do meditations on 3 more days that week to reach their goal of meditating daily.

- Date with partner: In week 1, they managed to go through their commitment have of having 1 date night that week; In week 2, they surpassed their quote of 1 date night/week, and had 2 date nights.

C. Their desired outcome was more happiness

- Happiness was initially rated as being at a 3/10, where 10 is the happiest they could possibly be, and 0 is the opposite.

- This patient’s scores mostly tracked sideways but showed signs of increasing slightly by the 2nd

- Note: it can take a few days or several weeks for increases in the desired outputs/rewards to catch up with persistently performing the inputs/efforts.

Boyer P. Evolutionary economics of mental time travel? Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:219–224.

Dubord, Greg. (2011). Part 3. The reward chart. Canadian family physician Médecin de famille canadien. 57. 201.

Martin, P. (1993). Psychological Management of Chronic Headaches: Treatment Manual for Practitioners. Guilford Press.

Schacter DL, Addis DR. The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory: Remembering the past and imagining the future. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007a;362:773–786.

Schacter DL, Addis DR. The ghosts of past and future. Nature. 2007b;445:27.

Suddendorf T, Corballis MC. Mental time travel and the evolution of the human mind. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr. 1997;123:133–167

Suddendorf T, Corballis MC. The evolution of foresight: What is mental time travel, and is it unique to humans? Behav Brain Sci. 2007;30:299–313.

Writing: Dr. Taher Chugh

Last update: March 2021